A research method examining a specific instance or phenomenon in depth offers both strengths and weaknesses. The ability to deeply investigate a complex issue within its real-life context is a primary benefit. This intensive analysis can provide rich, qualitative data, offering insights that might be missed by more superficial, quantitative approaches. However, the inherent subjectivity and lack of generalizability are notable limitations. Conclusions drawn from a single instance may not be applicable to other situations or populations.

The value of this approach lies in its capacity to generate hypotheses for future research and to provide detailed contextual understanding. Historically, disciplines such as medicine, law, and business have relied on this methodology to explore unusual or critical situations. By meticulously documenting and analyzing these occurrences, practitioners can develop best practices and refine their understanding of complex systems. Its strength is in its ability to provide a holistic view, especially when dealing with multifaceted problems.

The following discussion elaborates on the specific merits and demerits of this research approach, providing a balanced perspective on its application across various fields of study. Understanding both the positive and negative aspects is crucial for researchers when determining the appropriateness of this method for addressing their research questions.

Employing this method requires careful consideration of its inherent strengths and weaknesses. Strategic planning is paramount to maximizing its utility while mitigating potential pitfalls.

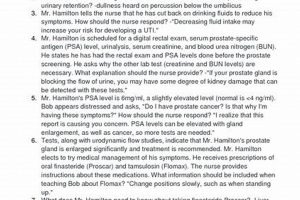

Tip 1: Define a Clear Research Question: A well-defined research question is crucial for guiding the data collection and analysis process. Without a clear focus, the depth of investigation can become unwieldy and lead to unfocused findings.

Tip 2: Establish Robust Data Collection Protocols: Implement systematic and rigorous data collection procedures to ensure the reliability and validity of the findings. Multiple sources of evidence, such as interviews, documents, and observations, should be used to triangulate data and reduce bias.

Tip 3: Acknowledge and Address Potential Biases: Recognize the inherent subjectivity and potential biases that can arise during data collection and interpretation. Implement strategies to mitigate these biases, such as engaging multiple researchers in the analysis process and employing transparent coding procedures.

Tip 4: Provide Thick Description: Offer a rich and detailed account of the instance being studied. This “thick description” allows readers to understand the context and nuances of the situation, enabling them to assess the transferability of the findings to other settings.

Tip 5: Articulate Limitations Explicitly: Clearly acknowledge the limitations of the research, including the lack of generalizability and the potential for researcher bias. Transparency in acknowledging limitations enhances the credibility of the research.

Tip 6: Focus on In-Depth Analysis, Not Breadth: Resist the temptation to overgeneralize or extrapolate findings beyond the specific context being studied. The strength lies in its ability to provide in-depth insights into a particular phenomenon, not to establish universal truths.

Tip 7: Consider a Mixed-Methods Approach: Integrate elements of quantitative research to complement the qualitative findings. Quantitative data can provide broader context and support the interpretation of the qualitative data.

Careful consideration of these points can substantially improve the rigor and relevance of the research, transforming a potentially weak methodology into a powerful analytical tool.

Therefore, understanding the multifaceted nature and careful execution are vital to produce meaningful and valuable research outputs.

1. In-depth exploration

In-depth exploration stands as a cornerstone of the research method. It is inextricably linked to its core strengths and weaknesses. This analytical intensity facilitates a profound understanding of complex phenomena within their natural settings. The thorough examination allows researchers to uncover intricate details and nuances that broader research methods might overlook. For instance, in organizational studies, an intense investigation of a company’s response to a crisis can reveal subtle organizational dynamics and decision-making processes that contribute to success or failure. This capacity for thorough analysis is a primary reason researchers opt for this methodology.

However, the very strength of exhaustive analysis contributes to its limitations. Time and resources are consumed in significant quantities. The deep dive also increases the potential for researcher bias, as prolonged engagement with the subject can inadvertently influence interpretation. Furthermore, the specificity of the findings can limit their generalizability. A detailed analysis of a single school’s reform efforts might provide valuable insights but may not be directly applicable to other schools facing different contextual realities. The relationship between exhaustive analysis and these limitations necessitates careful consideration of the trade-offs involved.

Ultimately, understanding the interplay between in-depth exploration and both the benefits and drawbacks of this approach is crucial for researchers. Recognizing that intense investigation simultaneously enables deep understanding and introduces potential biases allows for a more judicious application of this methodology. Mitigating the limitations through rigorous data collection and analysis protocols ensures that the benefits of thorough analysis are maximized while minimizing the risks of subjectivity and limited applicability.

2. Contextual Understanding

Contextual understanding is a critical element in research, exerting considerable influence on the method’s utility. The ability to interpret events and phenomena within their specific environment is a defining characteristic, shaping both its merits and demerits.

- Rich Data Interpretation

Contextual knowledge facilitates nuanced interpretation of data, allowing researchers to understand not just what happened, but why it happened in a particular way. For instance, examining a business failure requires understanding the economic climate, industry trends, and internal organizational dynamics that contributed to the outcome. This rich interpretation is a significant advantage, providing insights that might be missed by purely quantitative approaches. However, such interpretations can be subjective and depend heavily on the researcher’s understanding of the context.

- Relevance and Transferability

Understanding the context is crucial for assessing the relevance and transferability of findings. While a specific instance may not be directly generalizable, understanding the key contextual factors can help determine whether the insights might apply to other, similar situations. For example, understanding the cultural and social context of a successful educational program in one community can inform efforts to adapt the program to other communities with similar characteristics. However, overemphasizing the similarities and neglecting important differences can lead to inappropriate applications and potentially harmful outcomes.

- Identifying Complex Interrelationships

Contextual understanding allows researchers to identify complex interrelationships that might not be apparent through other research methods. Studying a community’s response to a natural disaster, for instance, requires understanding the interplay of social networks, government policies, and economic factors. This holistic perspective is a valuable advantage, but it also introduces complexity and increases the potential for confounding variables. Isolating the specific factors that contributed to the outcome can be challenging.

- Avoiding Misinterpretations

Lack of contextual awareness can lead to misinterpretations and inaccurate conclusions. Studying a historical event without understanding the prevailing social norms and political climate can result in a distorted view of the past. Thorough contextual research is essential to avoid such pitfalls, but it also requires significant effort and expertise. Researchers must be aware of their own biases and assumptions and strive to understand the perspectives of the people they are studying.

The degree of contextual understanding shapes the strength and limitations of research. It enhances interpretive power but introduces complexity and the potential for bias. A balanced approach, combining rigorous data collection with careful attention to context, is essential for maximizing the benefits and minimizing the risks. Therefore, understanding these intricate dynamics is fundamental for any researcher employing this methodology.

3. Limited generalizability

The limited potential for broad application represents a significant consideration when evaluating the merits and drawbacks of using a focused study. This characteristic, arising from the in-depth analysis of a specific instance, directly influences the utility of its findings in broader contexts. The intensive examination of a singular situation generates rich, context-specific data, valuable for understanding complex phenomena within defined boundaries. However, the very specificity that makes this method powerful simultaneously restricts its ability to produce universally applicable conclusions. For example, an analysis of successful turnaround strategies employed by a particular technology company may offer valuable insights into crisis management within that specific industry. However, directly transferring these strategies to a manufacturing firm facing different market conditions and organizational structures may prove ineffective or even detrimental.

The inherent challenge of translating findings from a highly specific instance to a wider population arises from the unique interplay of factors within the study’s scope. Variations in organizational culture, market dynamics, regulatory environments, and other contextual elements significantly impact the applicability of results. Consequently, researchers must exercise caution when attempting to extrapolate conclusions beyond the studied instance. While the detailed insights gained from one situation can inform hypotheses and provide valuable lessons, they should not be regarded as definitive or predictive of outcomes in dissimilar contexts. Instead, the emphasis should be on identifying transferable patterns or mechanisms that, when adapted to suit specific conditions, can contribute to informed decision-making. The limited generalizability is not necessarily a deficiency, rather a design feature, focusing analytical resources on depth rather than breadth. Thus, the understanding that these focused analyses are not intended to produce universal laws, but rather illuminate complex relationships within specific parameters, is crucial for appropriate application and interpretation.

In summary, the limited potential for wide application is a key element that determines the value of a focused research approach. While the depth of understanding generated can be invaluable, the inability to apply findings broadly necessitates careful consideration. Recognizing this inherent limitation allows researchers to manage expectations, avoid overgeneralizations, and leverage the method’s strengths for specific purposes, such as generating hypotheses for further investigation or informing context-sensitive interventions. The method is appropriate when deep, contextual understanding is prioritized over broad applicability, provided there is a clear acknowledgement of its constrained translational power.

4. Potential for bias

The presence of potential for bias constitutes a crucial consideration in evaluating the efficacy and reliability of investigations. Its influence permeates various stages of the research process, affecting data collection, analysis, and interpretation. Recognizing the ways in which bias can manifest is essential for mitigating its impact and ensuring the integrity of research findings. This is significant to the methods inherent strengths and weaknesses.

- Researcher Bias

Researcher bias arises from the investigator’s own preconceptions, beliefs, and values, which can inadvertently shape the research process. For example, a researcher studying the effectiveness of a particular educational program may unconsciously favor data that supports its success, while downplaying or ignoring contradictory evidence. This can lead to skewed interpretations and inaccurate conclusions. Mitigation strategies include reflexive journaling, peer debriefing, and the use of structured data collection protocols.

- Selection Bias

Selection bias occurs when the selection of the subject for in-depth analysis is not representative of the broader population, thereby limiting the generalizability of findings. If researchers selectively choose instances that conform to their pre-existing hypotheses, the resulting data may present a distorted view of the phenomenon under investigation. For example, if a study focuses solely on successful startups, it may fail to capture the factors that contribute to business failures. Random selection and careful consideration of inclusion/exclusion criteria are essential to minimize this form of bias.

- Information Bias

Information bias refers to systematic errors in the way data is collected or recorded. It can arise from leading questions in interviews, inaccurate record-keeping, or selective recall by participants. For example, in a retrospective study of patient outcomes, individuals may misremember details about their past medical treatments, leading to inaccurate data. Standardized data collection instruments and careful training of research personnel are crucial for minimizing information bias.

- Confirmation Bias

Confirmation bias is the tendency to seek out and interpret information that confirms pre-existing beliefs, while ignoring or downplaying contradictory evidence. This can occur both during data collection and analysis, leading researchers to selectively focus on findings that support their hypotheses. For example, a researcher studying the effects of climate change may selectively focus on data that supports the existence of human-caused global warming, while downplaying evidence that suggests other contributing factors. Critical self-reflection and peer review are important safeguards against confirmation bias.

The facets discussed underscore the pervasive potential for bias in this research approach. Although researchers cannot eliminate bias entirely, awareness and implementation of appropriate mitigation strategies are crucial for enhancing the credibility and validity of research findings. Recognizing these potential pitfalls and actively addressing them enables researchers to maximize the strengths of the methodology while minimizing its inherent weaknesses. It also helps decision-makers properly interpret the information extracted from this type of research.

5. Resource-intensive

The characteristic of being resource-intensive is inextricably linked to both the merits and demerits of employing a detailed research methodology. The significant investment of time, personnel, and financial resources required directly impacts the depth and scope of investigation achievable, thereby influencing the quality and utility of the findings. The time dedicated to comprehensive data collection, meticulous analysis, and contextual understanding contributes to the detailed insights that are a primary advantage of this method. For example, a longitudinal analysis of a community development program may require years of data collection, interviews, and observations, but the resultant understanding of the program’s long-term impact can be invaluable for informing future policy decisions. The extensive nature of such undertakings, however, presents a significant disadvantage, limiting the feasibility of this approach for researchers with constrained resources.

The demand for skilled personnel further amplifies the resource intensity. Conducting in-depth interviews, analyzing qualitative data, and interpreting complex contextual factors require expertise in research methods, data analysis, and the subject matter being studied. These skilled professionals command higher salaries and contribute significantly to the overall cost of the research. Furthermore, the potential for subjective interpretation necessitates the involvement of multiple researchers to ensure rigor and validity, further escalating personnel costs. Consider a legal study examining a specific court case: expert legal analysts, researchers, and potentially external consultants are needed to fully investigate all dimensions of the case. The benefit is the creation of detailed documentation, though the expenditure is significant.

The resource-intensive nature also influences the selection of the research methodology. Researchers often face a trade-off between the depth of investigation and the breadth of coverage. Due to financial and logistical constraints, a large-scale quantitative study involving a broad sample may be more feasible than a thorough investigation of a single instance. This decision is often driven by the specific research question and the available resources. The understanding of its implications are crucial in planning and interpreting results. Properly allocating resources, acknowledging limitations, and focusing on a manageable scope are key strategies for maximizing the value of this approach despite the inherent demands on resources.

6. Subjectivity concerns

Subjectivity, the influence of personal feelings, tastes, or opinions, is a central consideration when evaluating the research method. Its presence profoundly affects both the potential value and the inherent limitations, demanding careful attention and mitigation strategies throughout the research process.

- Researcher Interpretation

The researcher’s perspective inevitably shapes the interpretation of data. Unlike quantitative methods that rely on numerical objectivity, qualitative approaches require researchers to make judgments about the significance of observations, interview responses, and documents. For example, in analyzing interview transcripts, a researcher’s preconceived notions about a particular social issue could influence the way they categorize and interpret participant statements. This inherent subjectivity can lead to biased findings and limit the generalizability of results. The use of multiple coders and transparent coding procedures can help mitigate this risk.

- Participant Bias

The participants’ subjective experiences and perspectives also influence the data. Individuals may selectively recall events, present themselves in a favorable light, or withhold information for various reasons. For example, in a study of organizational culture, employees may be hesitant to voice negative opinions about their workplace for fear of repercussions. This can distort the data and undermine the validity of the findings. Researchers must be aware of these potential biases and employ techniques, such as building rapport and ensuring confidentiality, to encourage honest and open communication.

- Lack of Standardization

The absence of standardized procedures in data collection and analysis contributes to subjectivity concerns. Unlike structured surveys or experiments, the method often involves flexible and open-ended data collection methods, such as interviews and observations. This allows researchers to explore complex issues in depth, but it also introduces the potential for inconsistencies and biases. For example, the questions asked in an interview may vary depending on the interviewer’s style and the participant’s responses, making it difficult to compare data across different instances. Clear articulation of data collection protocols is vital.

- Contextual Dependence

The context-specific nature of the research further exacerbates subjectivity concerns. Findings are often deeply embedded in the particular context being studied, making it difficult to separate the effects of specific interventions from the broader environment. For example, in a study of a school reform initiative, it may be challenging to determine whether improvements in student outcomes are due to the reform program itself or to other factors, such as changes in demographics or community resources. Researchers must carefully consider the influence of contextual factors and acknowledge the limitations of their findings.

These elements highlight the inherent subjectivity of research, underscoring the importance of acknowledging and addressing these concerns throughout the research process. While complete objectivity is unattainable, transparency, rigorous methods, and critical self-reflection can enhance the credibility and trustworthiness of findings.

7. Hypothesis generation

Hypothesis generation serves as a crucial function within the realm of research. The method’s inherent capacity to foster the development of new research questions and tentative explanations is inextricably linked to its advantages and disadvantages. Detailed analysis of a specific phenomenon often reveals patterns or anomalies that would otherwise remain unnoticed. For example, an in-depth analysis of a company experiencing rapid growth might reveal previously unrecognized factors contributing to its success, leading to the formulation of hypotheses about the role of specific leadership styles or organizational structures in driving rapid expansion. This generative capacity is a primary advantage, offering fertile ground for future research endeavors. The generation of hypotheses in this manner stems directly from the detailed contextual understanding that the research method provides. The intense focus on a singular instance allows for the identification of nuanced relationships and potential causal mechanisms that may not be apparent in broader, quantitative studies.

However, the hypotheses generated within the method framework are inherently limited by the specific context from which they arise. While a hypothesis regarding leadership styles derived from the study of one successful company may be intriguing, its direct applicability to other organizations or industries cannot be assumed. The potential for overgeneralization is a significant disadvantage, highlighting the need for further testing and validation using alternative research methods. The hypotheses generated in this manner are not intended as definitive explanations, but rather as starting points for more rigorous investigation. In medical research, the observation of an unexpected positive outcome in a single patient treated with a novel drug can lead to the formulation of a hypothesis about the drug’s potential efficacy. However, this hypothesis must be rigorously tested in clinical trials to determine whether the effect is genuine and generalizable.

In summary, hypothesis generation is a vital outcome within a detailed research approach, offering a pathway for exploration. Although subject to inherent limitations, such as potential overgeneralization, the ability to formulate new research questions based on in-depth observation remains a significant strength. The proper utilization of this outcome requires a clear understanding of its context-specific nature and a commitment to further testing and validation using complementary research methodologies. The method’s utility lies in its capacity to identify potentially fruitful areas for future research, rather than to provide definitive answers. Thus, understanding the function of hypothesis generation as a component of research is vital for appropriately interpreting its outcomes.

Frequently Asked Questions Regarding Application Merits and Demerits

The following addresses common queries and concerns regarding the research method involving detailed examination of single instances or occurrences.

Question 1: How can findings from one singular instance be relevant to other situations?

Relevance stems from identifying transferable patterns, mechanisms, or theoretical insights. While direct generalization is inappropriate, the detailed analysis may reveal fundamental principles that, when adapted, can inform understanding and decision-making in similar contexts.

Question 2: What measures can be taken to mitigate the potential for bias in research?

Bias mitigation strategies include employing multiple researchers for data analysis, using structured data collection protocols, engaging in reflexive journaling to acknowledge personal biases, and seeking peer debriefing to challenge interpretations.

Question 3: Is there a specific field where a study approach is particularly well-suited?

This method proves especially effective when dealing with multifaceted problems or innovative situations. Fields like medicine, law, business, and education often leverage it to explore complex scenarios and generate insights.

Question 4: How does one balance the need for depth with the limitations of limited scope when using this research approach?

Balance can be achieved by clearly defining the research question, establishing rigorous data collection protocols, and explicitly articulating the limitations of the research. The goal should be to provide in-depth insights within a well-defined scope.

Question 5: What distinguishes from other methodologies such as surveys or experiments?

Unlike surveys or experiments that focus on breadth and statistical generalizability, a detailed examination of single instances prioritizes depth, contextual understanding, and nuanced interpretation. It’s qualitative, not quantitative, emphasizing meaning over measurement.

Question 6: If the goal is to establish universal truths, is this method appropriate?

No, it’s not appropriate for establishing universal truths. This approach is best used when the goal is to generate hypotheses, explore complex phenomena within specific contexts, or inform context-sensitive interventions. It is not designed to produce broad generalizations.

Understanding the specific utility and inherent limitations is crucial for effective implementation. Judicious application ensures the research contributes valuable, context-rich insights.

The subsequent section will delve into practical examples, further illustrating the strategic implementation of a detailed research method.

Conclusion

The preceding discussion has presented a comprehensive overview of the methodology involving detailed examination of specific instances. The “advantages and disadvantages of case study” are characterized by a tension between the capacity for in-depth contextual understanding and the limitations regarding generalizability and potential for bias. The method’s ability to generate hypotheses and uncover nuanced insights is balanced by the resource-intensive nature and the inherent subjectivity concerns that must be carefully addressed.

Ultimately, the utility of this approach depends on a clear understanding of its strengths and weaknesses and a strategic alignment with the research objectives. Researchers are encouraged to carefully consider these factors when selecting a methodology, ensuring that the chosen approach is well-suited to the specific research question and the available resources. The ongoing refinement and critical evaluation of research practices will continue to shape the application of this valuable, yet complex, analytical tool.