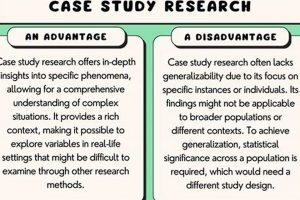

Case study research, while offering valuable in-depth analysis, is not without its limitations. A primary concern is the potential for limited generalizability. Findings derived from a single case, or even a small collection of cases, may not be representative of broader populations or phenomena. For example, conclusions drawn from a detailed examination of a particularly successful business innovation may not be applicable to other organizations operating in different markets or with varying resources.

Understanding the constraints of this research approach is crucial for researchers and decision-makers alike. Recognizing these limitations allows for a more nuanced interpretation of the findings and informs decisions regarding the appropriateness of this methodology. Historically, the lack of broader applicability has prompted criticism, leading to calls for greater methodological rigor and careful consideration of the context within which a case is examined. The singular nature of the case can, therefore, limit the conclusions that may be reached.

The following sections delve into specific aspects that may impede the effective use of case study methodology, including challenges related to bias, resource intensiveness, and difficulties in establishing causality. Each factor plays a significant role in assessing the utility of case study research within a given context. Further exploration is required to understand the limitations inherent in this method.

Mitigating the Impact of Case Study Limitations

Recognizing the inherent constraints associated with case study research is paramount to maximizing its utility and minimizing potential drawbacks. The following guidelines offer strategies to address common criticisms and enhance the rigor of case study investigations.

Tip 1: Employ Multiple Cases for Enhanced Generalizability: While a single case offers depth, the inclusion of multiple cases, selected strategically, can improve the breadth and robustness of the findings. This approach facilitates cross-case analysis, allowing for the identification of patterns and commonalities that strengthen the overall conclusions.

Tip 2: Clearly Define the Scope and Boundaries of the Case: Ambiguity regarding the scope of the investigation can lead to unfocused analysis and difficulty in drawing meaningful conclusions. Prior to commencing the research, establish clear boundaries for the case, specifying the timeframe, actors, and relevant contexts to be examined.

Tip 3: Implement Rigorous Data Collection and Analysis Procedures: To minimize bias and enhance the credibility of the findings, adopt systematic data collection methods, such as structured interviews, document analysis, and direct observation. Employ established analytical frameworks to ensure a thorough and objective interpretation of the data.

Tip 4: Address Potential Researcher Bias Proactively: Acknowledge the potential for researcher bias and implement strategies to mitigate its influence. This may involve triangulation of data sources, peer review of findings, and reflexivity on the part of the researcher to identify and address their own assumptions and preconceptions.

Tip 5: Articulate the Limitations of the Study Transparently: Rather than attempting to conceal the constraints of the case study, explicitly acknowledge them in the research report. Transparency regarding the limitations enhances the credibility of the study and allows readers to critically evaluate the findings within their appropriate context.

Tip 6: Focus on Theoretical Generalization Rather Than Statistical Generalization: Case studies are often better suited for contributing to theory development rather than generating statistically generalizable findings. Frame the research question and analysis in terms of its potential to refine or extend existing theoretical frameworks.

These strategies collectively contribute to a more robust and defensible case study research design. By addressing the potential drawbacks proactively, researchers can enhance the value and impact of their investigations.

By carefully considering and addressing these points, one can navigate the weaknesses of case studies, thereby increasing the effectiveness and validity of the study.

1. Limited Generalizability

Within the framework of case study drawbacks, limited generalizability emerges as a primary concern. The intensive focus on a specific instance, whether an organization, event, or individual, restricts the extent to which findings can be extrapolated to broader contexts. The richness of detail, while valuable for understanding the case itself, often comes at the expense of broader applicability, thereby impacting the overall validity of conclusions.

- Context-Specific Factors

The uniqueness of each case, shaped by specific historical, environmental, and organizational factors, hinders the direct transfer of insights. A successful intervention in one setting might fail in another due to differing cultural norms, resource availability, or leadership styles. This variability underscores the challenges of applying lessons learned from a particular case study to other, dissimilar situations. For instance, a turnaround strategy that worked for a technology firm in Silicon Valley might not be effective for a manufacturing company in the Midwest due to differing economic climates and workforce characteristics.

- Sample Size Limitations

Case studies often involve small sample sizes, frequently focusing on a single entity. This limited number of observations reduces the statistical power of the findings and prevents the application of standard statistical inference techniques. Conclusions drawn from one or a few cases may be idiosyncratic, reflecting the unique circumstances of those specific instances rather than representing broader trends or patterns. Attempting to generalize from a sample size of one, regardless of the depth of analysis, carries a significant risk of drawing inaccurate or misleading conclusions.

- Selection Bias

The selection of cases for study can introduce bias, particularly if cases are chosen based on their perceived success or uniqueness. This deliberate selection of exceptional cases can skew the findings and limit their applicability to more typical or average situations. For example, studying only high-performing companies might provide insights into best practices but fails to address the challenges faced by struggling organizations. The resulting analysis, therefore, may not be representative of the wider population of organizations, impacting the validity of any generalizations.

- Lack of Statistical Rigor

Case study research typically relies on qualitative data, such as interviews, observations, and document analysis, rather than quantitative data amenable to statistical analysis. This reliance on qualitative methods makes it difficult to quantify the strength of relationships or assess the statistical significance of findings. While qualitative data can provide rich insights, it lacks the statistical rigor necessary to support broad generalizations. The subjective nature of qualitative analysis further contributes to the challenge of establishing the generalizability of case study findings.

The constraint of limited generalizability underscores a critical consideration in evaluating case study research. While the depth of understanding gained from a case study can be invaluable, it’s crucial to acknowledge the limitations on extrapolating findings to other contexts. This awareness is essential for appropriately interpreting and applying the insights derived from case study investigations.

2. Potential for bias

The presence of bias constitutes a significant concern within case study research, directly contributing to its limitations. Various forms of bias can infiltrate the research process, impacting data collection, analysis, and interpretation, ultimately undermining the validity and reliability of the findings.

- Researcher Bias

Researcher bias arises from the preconceptions, beliefs, or personal experiences that a researcher brings to the study. This can manifest in selective data collection, where the researcher focuses on evidence that supports their pre-existing hypotheses while disregarding contradictory information. It can also influence data interpretation, leading to biased conclusions that align with the researcher’s viewpoint rather than the objective evidence. For example, a researcher studying the success of a particular leadership style might selectively highlight positive outcomes while downplaying negative consequences, thereby distorting the overall picture.

- Participant Bias

Participant bias occurs when individuals involved in the case study provide inaccurate or incomplete information due to social desirability, memory distortions, or strategic motivations. Interviewees may present themselves in a favorable light, concealing negative aspects or exaggerating positive achievements. Similarly, access to information within an organization may be selectively granted or denied based on political considerations, skewing the researcher’s understanding of the situation. This bias can be particularly problematic in sensitive or controversial cases, where participants may be reluctant to disclose truthful information.

- Selection Bias

Selection bias emerges when the cases chosen for study are not representative of the broader population of interest. This can occur if cases are selected based on their perceived success, uniqueness, or accessibility, rather than on a systematic and unbiased sampling strategy. For example, a case study focusing solely on successful startups might provide valuable insights into entrepreneurial best practices but fails to capture the challenges and failures experienced by the majority of startups. The resulting findings, therefore, may not be generalizable to the wider population of startups, limiting the applicability of the conclusions.

- Confirmation Bias

Confirmation bias is the tendency to seek out and interpret evidence in a way that confirms pre-existing beliefs or hypotheses. This can lead researchers to selectively focus on data that supports their initial assumptions while ignoring or downplaying contradictory evidence. For example, a researcher investigating the effectiveness of a particular educational program might selectively focus on positive student outcomes while overlooking negative feedback or evidence of unintended consequences. This can result in a distorted and incomplete understanding of the program’s true impact.

These different sources of bias highlight the inherent challenges in maintaining objectivity within case study research. Left unaddressed, these biases can severely compromise the validity and reliability of the findings, undermining the credibility and value of the research. Vigilance, transparency, and the implementation of rigorous research protocols are essential for minimizing the impact of bias and ensuring the integrity of case study investigations.

3. Time-consuming nature

The intensive data collection and analysis inherent in case study research render it a notably time-consuming endeavor, contributing significantly to its inherent limitations. The depth of investigation required to develop a comprehensive understanding of the case necessitates substantial investment of time and resources, impacting the feasibility and practicality of this approach.

- Extensive Data Collection

Gathering sufficient data to provide a rich and detailed understanding of a case necessitates diverse data sources and methods. This frequently involves conducting in-depth interviews with multiple stakeholders, reviewing extensive documentation, and potentially undertaking direct observation over extended periods. Securing access to relevant data and coordinating these activities can be logistically challenging and demand considerable time investment. The volume of information generated from these sources then requires careful organization and management, adding to the overall duration of the research.

- In-Depth Analysis and Interpretation

The qualitative nature of much of the data collected in case study research necessitates rigorous analysis and interpretation. Transcribing and coding interviews, identifying patterns and themes within documents, and constructing a coherent narrative from disparate sources requires substantial intellectual effort and time. The iterative nature of the analysis process, involving repeated cycles of data review and interpretation, further extends the duration of the research. The subjective nature of the analysis also necessitates careful consideration of alternative interpretations, adding complexity and time to the process.

- Transcription and Coding Processes

A core component of qualitative data analysis within case studies often involves transcribing interviews and coding the resulting text. This process alone is extremely labor-intensive, with each hour of interview audio typically requiring several hours of transcription. The subsequent coding phase, where researchers assign labels or categories to segments of text to identify patterns and themes, further adds to the time burden. Effective coding requires careful attention to detail, consistency in application, and potentially the involvement of multiple coders to ensure inter-rater reliability, all of which contribute to the overall time investment.

- Report Writing and Dissemination

Synthesizing the findings of a case study into a coherent and compelling report also requires significant time and effort. The report must present a detailed narrative of the case, supported by evidence from the data, and articulate the key insights and implications of the research. Drafting, revising, and editing the report to ensure clarity, accuracy, and persuasiveness can be a lengthy process. Furthermore, disseminating the findings through academic publications or other channels may involve additional time investment in preparing manuscripts, responding to reviewer comments, and presenting the research at conferences.

The protracted timeframe associated with case study research presents practical challenges for researchers and organizations considering this approach. The time investment may exceed available resources, leading to compromises in the scope or depth of the investigation. In time-sensitive situations, the lengthy duration of case study research may render it impractical, as the findings may not be available in time to inform critical decisions. Thus, careful consideration of the time commitment is essential when evaluating the suitability of case study methodology.

4. Difficult causal inferences

Establishing definitive cause-and-effect relationships represents a significant hurdle within case study research, thereby highlighting a crucial disadvantage of this methodological approach. The inherent complexity of real-world settings, coupled with the lack of experimental control, complicates the process of isolating specific causal factors and attributing outcomes directly to particular interventions or events. This limitation necessitates careful consideration when interpreting findings and drawing conclusions from case studies.

- Confounding Variables

The presence of numerous confounding variables within a case study environment undermines the ability to isolate the impact of any single factor. These extraneous variables, often unmeasured or unacknowledged, can influence the outcome of interest, obscuring the true relationship between the presumed cause and its purported effect. For instance, attributing the success of a business strategy solely to a new marketing campaign might overlook the concurrent influence of economic conditions, competitor actions, or internal organizational changes. Such uncontrolled variables introduce ambiguity and weaken the validity of causal claims.

- Temporal Ambiguity

Determining the precise temporal sequence of events can prove challenging in case study research, further complicating causal inference. Establishing whether a presumed cause preceded its supposed effect is critical for supporting a causal relationship. However, the retrospective nature of many case studies, coupled with the reliance on potentially incomplete or biased historical data, can make it difficult to ascertain the accurate order of events. This temporal ambiguity undermines the ability to confidently assert that one factor caused another, as the reverse relationship or the influence of a third, unobserved factor cannot be ruled out.

- Lack of Control Group

The absence of a control group, a hallmark of experimental designs, fundamentally limits the ability to draw causal inferences from case studies. Without a comparable group that did not receive the intervention or experience the event of interest, it is impossible to determine whether the observed outcome would have occurred regardless. For example, assessing the effectiveness of a new educational program without a control group to compare student performance against makes it difficult to ascertain whether the program itself was responsible for any observed improvements or whether those gains would have occurred naturally due to other factors, such as student motivation or prior academic preparation.

- Reverse Causation

The possibility of reverse causation represents a further complication in establishing causal relationships within case studies. Reverse causation occurs when the presumed effect actually causes the supposed cause. For example, a study examining the relationship between employee satisfaction and productivity might find a correlation between the two. However, it could be that increased productivity leads to greater employee satisfaction, rather than the other way around. Disentangling the direction of causality requires careful analysis and consideration of alternative explanations, adding to the challenges of drawing definitive causal inferences.

The inherent difficulties in establishing causal inferences underscore a significant constraint on the utility of case study research for answering questions of cause and effect. While case studies can provide valuable insights into the complexities of real-world phenomena, the inability to definitively establish causal relationships necessitates caution in interpreting findings and generalizing conclusions. Researchers must acknowledge these limitations and employ rigorous analytical techniques to strengthen the plausibility of their causal claims, even if definitive proof remains elusive.

5. Replicability challenges

Replicability, the ability to reproduce research findings consistently across independent investigations, presents a substantial obstacle within case study methodology, thereby amplifying its disadvantages. The contextual specificity and qualitative nature of case study research often impede attempts to replicate findings, limiting their generalizability and raising questions about their reliability.

- Uniqueness of Context

Each case study inherently operates within a unique context, shaped by specific historical, organizational, and environmental factors. These context-specific elements are often difficult, if not impossible, to replicate precisely in another setting. The interplay of these contextual variables influences the outcomes observed in a particular case, making it challenging to determine whether similar results would occur in a different context. The irreproducibility of these contextual conditions undermines the ability to replicate the findings and generalize them to other situations. For instance, a case study examining the implementation of a specific management practice in one company may not be replicable in another due to differences in organizational culture, leadership styles, or industry dynamics. This uniqueness challenges the external validity of the study.

- Subjectivity in Data Interpretation

Case study research often relies heavily on qualitative data, such as interviews, observations, and document analysis, which are inherently subject to interpretation. Different researchers may interpret the same data in different ways, leading to varying conclusions. This subjectivity in data interpretation makes it difficult to replicate the analysis process and obtain consistent results. The potential for researcher bias further exacerbates this challenge, as researchers may selectively focus on evidence that supports their pre-existing hypotheses, leading to divergent interpretations of the same case. This variability in interpretation undermines the reliability and replicability of the findings. For example, when examining a companys failure, different researchers might emphasize the companys internal conflicts, external economic pressures, or a combination of both.

- Lack of Standardized Protocols

Unlike experimental research, case study methodology often lacks standardized protocols for data collection and analysis. The flexible and exploratory nature of case study research allows researchers to adapt their methods to the specific circumstances of the case. However, this lack of standardization can make it difficult to replicate the research process. Different researchers may employ different data collection techniques, use different interview questions, or apply different analytical frameworks, leading to divergent results. The absence of consistent procedures makes it challenging to compare findings across different case studies and to establish the reliability and replicability of the research.

- Difficulty in Controlling Variables

Case study research typically occurs in naturalistic settings, where researchers have limited control over extraneous variables. This lack of experimental control makes it difficult to isolate the factors that contribute to the observed outcomes. Attempts to replicate a case study in a different setting may be confounded by uncontrolled variables that were not present in the original case. The inability to control for these extraneous factors undermines the ability to determine whether the observed results are truly replicable or simply due to chance variations in the research environment. The presence of uncontrolled variables compromises the internal validity and replicability of the study. Its hard to replicate the exact market conditions that a previous study observed.

These replicability challenges further underscore the limitations of case study research. While case studies can provide valuable insights into complex phenomena, the difficulties in replicating findings necessitate caution in generalizing conclusions and applying them to other contexts. Recognizing these limitations is essential for appropriately interpreting case study findings and for designing future research that addresses these methodological challenges.

6. Subjectivity of interpretation

Subjectivity of interpretation significantly amplifies the drawbacks inherent in case study research. The inherent qualitative nature of case studies necessitates that researchers engage in interpretation, drawing meaning from textual and observational data. This interpretive process, however, is influenced by the researcher’s pre-existing beliefs, theoretical frameworks, and personal experiences. Consequently, even with rigorous methodologies, the same case data can yield divergent conclusions depending on the interpretive lens applied, undermining the objectivity and reliability of the findings.

The impact of subjective interpretation manifests in various ways. During data collection, researchers may unconsciously prioritize information that aligns with their preconceived notions, leading to a selective focus on supporting evidence while downplaying contradictory data. During the analysis phase, the coding and categorization of qualitative data are subject to researcher judgment, potentially introducing bias into the identification of patterns and themes. For instance, in a case study examining organizational culture, a researcher with a background in behavioral psychology might emphasize individual motivations and interpersonal dynamics, while a researcher trained in sociology might focus on broader social structures and power relations. This divergence in perspective inevitably shapes the interpretation of the data and the conclusions drawn about the organization’s culture. A real-world example is the analysis of historical events, where historians often present conflicting interpretations based on the same set of documents and artifacts, illustrating the challenges of achieving objective understanding. The practical significance of acknowledging this subjectivity lies in the need for transparency regarding the researcher’s theoretical framework and the potential biases that might influence the interpretation of the case data. This transparency allows readers to critically evaluate the findings and assess the validity of the conclusions.

Addressing the challenge of subjective interpretation requires a multi-faceted approach. Triangulation, involving the use of multiple data sources and methods, can help to mitigate bias by providing a more comprehensive and nuanced understanding of the case. Peer review, where independent researchers scrutinize the data analysis and interpretation, can identify potential biases and alternative interpretations. Furthermore, researchers should explicitly articulate their theoretical framework and acknowledge any potential biases that might influence their analysis. While complete objectivity may be unattainable, these measures can enhance the credibility and trustworthiness of case study findings, ultimately reducing the negative impact of subjective interpretation on the overall validity of the research.

Frequently Asked Questions Regarding Case Study Limitations

This section addresses common queries surrounding the drawbacks associated with case study methodology, providing clear and concise answers to facilitate informed decision-making regarding its application.

Question 1: How significantly does limited generalizability impact the value of a case study?

Limited generalizability restricts the extent to which findings from a specific case can be applied to broader populations or contexts. This constraint necessitates careful consideration of the case’s representativeness and the potential for contextual factors to influence the results. The value of a case study, therefore, lies primarily in its in-depth exploration of a specific instance, offering valuable insights that may inform theory development or future research, rather than providing statistically generalizable conclusions.

Question 2: What steps can be taken to mitigate the potential for bias in case study research?

Mitigating bias requires a rigorous and systematic approach. Researchers should employ triangulation, using multiple data sources and methods to corroborate findings. Explicitly acknowledging and addressing potential researcher biases is crucial. Independent peer review of data analysis and interpretation can further enhance objectivity. Adherence to established research protocols and transparent reporting of methodological choices are essential for minimizing the influence of bias on the results.

Question 3: Why is the time-consuming nature of case studies considered a disadvantage?

The extensive data collection and analysis inherent in case study research demand significant time and resources. This prolonged duration can limit the feasibility of the approach, particularly when timely insights are required. The time investment may also strain available resources, potentially compromising the scope or depth of the investigation. The protracted timeline poses practical challenges for researchers and decision-makers operating under time constraints.

Question 4: What are the implications of difficult causal inferences for case study conclusions?

The difficulty in establishing definitive cause-and-effect relationships necessitates caution in interpreting case study findings. While case studies can reveal associations between variables, they cannot definitively prove causality due to the lack of experimental control and the presence of confounding factors. The findings, therefore, should be interpreted as suggestive rather than conclusive, and further research may be required to validate causal claims.

Question 5: How do replicability challenges affect the credibility of case study research?

Replicability challenges raise concerns about the reliability and generalizability of case study findings. The unique contextual factors and subjective interpretations inherent in case studies make it difficult to reproduce the results in different settings. This limitation raises questions about the extent to which the findings can be confidently applied to other cases. Enhanced transparency in reporting research methods and contextual details can improve replicability, but inherent challenges remain.

Question 6: How does subjectivity of interpretation influence the validity of case study findings?

The subjectivity of interpretation introduces a potential source of bias into case study research. The researcher’s pre-existing beliefs and theoretical frameworks can influence the analysis and interpretation of data, leading to divergent conclusions. Addressing this challenge requires explicit articulation of the researcher’s perspective, triangulation of data sources, and peer review to identify potential biases and alternative interpretations. While subjectivity cannot be entirely eliminated, these measures can enhance the trustworthiness of the findings.

Recognizing and addressing these common concerns is crucial for maximizing the value and minimizing the potential drawbacks of case study research. A thorough understanding of these limitations allows for a more nuanced and informed application of this methodology.

The subsequent discussion explores alternative research approaches that may offer advantages in specific contexts.

Disadvantages of Case Study

This exploration has detailed the multifaceted nature of the disadvantages of case study research. From limited generalizability and the potential for bias to the time-consuming nature, difficulties in establishing causality, replicability challenges, and subjectivity of interpretation, the inherent limitations of this methodology warrant careful consideration. These factors collectively influence the suitability of case studies for addressing specific research questions and interpreting their findings responsibly.

Acknowledging these constraints is paramount for researchers and decision-makers alike. A comprehensive understanding of these limitations allows for a more nuanced assessment of the value and applicability of case study findings. Continued refinement of methodological approaches and a transparent recognition of inherent limitations will be crucial to maximizing the potential of case study research while mitigating its inherent disadvantages. This critical awareness will foster more informed and effective utilization of case study methods in diverse fields of inquiry.