Methods employed to investigate the distribution and determinants of health-related states or events in specified populations are diverse and critical to understanding disease patterns. These methodologies provide frameworks for researchers to systematically examine the causes and risk factors associated with various health outcomes. For instance, a controlled trial may be used to evaluate the efficacy of a new pharmaceutical intervention, while a cohort study could track the incidence of a particular disease over time in a defined population.

The systematic application of these research approaches provides essential evidence for informing public health policy and practice. The insights gained facilitate the development of targeted prevention strategies, the implementation of effective interventions, and the allocation of resources to address the most pressing health challenges. Historically, rigorous application of these methods has led to landmark discoveries, such as identifying the link between smoking and lung cancer and understanding the transmission routes of infectious diseases. This, in turn, strengthens the foundation of evidence-based public health decision-making, leading to improved population health outcomes.

The subsequent sections will delve into the specific types of methodologies used, covering descriptive, analytical, and interventional approaches. These discussions will explore the strengths and limitations of each type and their appropriate application in various public health scenarios. Focus will be given on how these research strategies address different types of questions, and guide future investigation in healthcare and medicine to improve health outcomes.

Guidance for Methodological Application

The following provides insights into the appropriate application of various research methodologies in public health and clinical research.

Tip 1: Define Clear Research Objectives: Prior to selecting a specific methodology, articulate well-defined research questions and hypotheses. This ensures that the chosen design is aligned with the study’s goals and can effectively address the intended outcomes. For example, determining whether the objective is to describe disease prevalence or to assess the impact of a new treatment will significantly influence the methodological choice.

Tip 2: Consider the Temporal Relationship: Account for the time sequence of events when selecting a design. Prospective studies are well-suited for examining potential causes of disease, while retrospective studies are often used to investigate rare outcomes or outcomes with long latency periods. For instance, a case-control study is more efficient for investigating rare diseases than a prospective cohort study.

Tip 3: Address Potential Biases: Implement measures to minimize potential sources of bias, such as selection bias, information bias, and confounding. Stratification, matching, and multivariable regression techniques can be employed to control for confounding variables and reduce the impact of bias on study results. Blinding the participants and the investigators also can reduce bias.

Tip 4: Ensure Adequate Sample Size: Calculate the necessary sample size to achieve sufficient statistical power to detect meaningful associations. Underpowered studies may fail to identify true effects, whereas overpowered studies can waste resources. Factors influencing sample size include the expected effect size, the desired level of statistical significance, and the variability of the outcome measure.

Tip 5: Adhere to Ethical Principles: Uphold ethical standards in all aspects of research, including informed consent, confidentiality, and data security. Research protocols should be reviewed and approved by an institutional review board (IRB) to ensure the protection of human subjects and the responsible conduct of research.

Tip 6: Employ Appropriate Statistical Analysis: Select statistical methods that are appropriate for the type of data and research question. Use caution when interpreting p-values. Consider the clinical significance and practical implications of research findings. Consulting with a biostatistician is highly recommended to ensure proper methods and interpretations.

Careful consideration of these guiding principles will enhance the rigor, validity, and interpretability of investigations, leading to more robust evidence for informing public health practice and policy.

In conclusion, strategic implementation and critical evaluation of findings will greatly improve the translation of research into meaningful action, contributing to enhanced population health.

1. Descriptive Epidemiology

Descriptive epidemiology forms a foundational component of epidemiological research, functioning as an initial stage in the investigation of health-related phenomena. It systematically characterizes the distribution of diseases and health conditions within populations, providing essential context for subsequent analytical studies. By examining patterns of disease occurrence according to person, place, and time, descriptive methods generate hypotheses about potential risk factors and causal mechanisms. For example, observing a higher incidence of a specific cancer within a particular geographic region or demographic group prompts further investigation into environmental or lifestyle factors that may contribute to its development.

The information gathered through descriptive approaches directly influences the selection and design of analytical investigations. If descriptive data reveal a temporal trend in disease incidence, analytical studies might focus on identifying exposures that have changed over time and correlate with the observed trend. Similarly, if differences in disease prevalence are noted across different subgroups, analytical studies can be designed to compare these subgroups and identify potential risk factors. A classic example is the observation of a clustering of cholera cases in London during the 1854 outbreak, which led John Snow to hypothesize and subsequently demonstrate the link between cholera transmission and contaminated water sources. This illustrates how thorough descriptive analyses are integral to formulating focused research questions.

In conclusion, descriptive epidemiology provides the essential groundwork for more in-depth epidemiological investigations. By systematically characterizing disease patterns, it guides the formulation of hypotheses, informs the design of analytical studies, and ultimately contributes to the development of effective public health interventions. This type of study is an indispensable initial step, enabling researchers to effectively explore causal relationships and address pressing health challenges.

2. Analytical Epidemiology

Analytical epidemiology represents a critical phase within the broader context, moving beyond mere description to actively investigate the determinants of health outcomes. It aims to identify and quantify the associations between exposures and diseases, providing insights into the causal mechanisms that underpin public health challenges.

- Cohort Studies

Cohort studies prospectively follow groups of individuals with differing exposures to determine the incidence of specific diseases. For example, the Framingham Heart Study has tracked a cohort of residents since 1948, yielding critical information on risk factors for cardiovascular disease, such as high cholesterol and smoking. These studies help establish temporal relationships, demonstrating that exposure precedes outcome, an essential element in causal inference.

- Case-Control Studies

Case-control studies retrospectively compare individuals with a disease (cases) to a comparable group without the disease (controls) to identify prior exposures. This approach is particularly useful for investigating rare diseases. For instance, case-control studies have been instrumental in identifying the association between diethylstilbestrol (DES) exposure in utero and the subsequent development of clear cell adenocarcinoma of the vagina in daughters of women who took DES during pregnancy.

- Cross-Sectional Studies

Cross-sectional studies examine the prevalence of diseases and exposures at a single point in time. While they cannot establish causality, they provide valuable information on the distribution of health conditions and can identify potential associations that warrant further investigation. A national health survey, for example, can reveal the prevalence of obesity and related risk factors within a population, informing public health interventions.

- Ecological Studies

Ecological studies examine the relationship between exposures and outcomes at the population level, rather than at the individual level. For instance, researchers might compare cancer rates in different regions with varying levels of air pollution. While these studies are prone to ecological fallacy (inferring individual-level associations from population-level data), they can be useful for generating hypotheses and identifying potential environmental risk factors.

The choice of approach depends on the research question, available resources, and ethical considerations. Cohort studies are stronger for establishing causality but can be resource-intensive and time-consuming. Case-control studies are more efficient for rare diseases but are susceptible to recall bias. Careful consideration of these trade-offs is essential for selecting the most appropriate study design and drawing valid conclusions about the determinants of health outcomes.

3. Experimental Studies

Experimental studies represent a critical subset within epidemiological study designs, distinguished by the researcher’s active manipulation of an exposure to observe its effect on a health outcome. This intervention-based approach allows for a more direct assessment of causality compared to observational designs, although it also presents unique ethical and practical considerations.

- Randomized Controlled Trials (RCTs)

RCTs are considered the gold standard for evaluating the efficacy of interventions. Participants are randomly assigned to either an intervention group or a control group, minimizing selection bias and allowing for a more accurate comparison of outcomes. The Polio vaccine trials of the 1950s are a prime example, where random assignment to vaccine or placebo groups definitively demonstrated the vaccine’s effectiveness. The rigorous control in RCTs enables stronger causal inferences and informs evidence-based practice guidelines.

- Community Intervention Trials

Community intervention trials extend the experimental approach to entire communities or groups, rather than individuals. These trials evaluate the impact of public health programs or policies on population-level outcomes. An example includes the Stanford Five-City Project, which evaluated a community-based cardiovascular disease prevention program through interventions targeting diet, smoking, and physical activity. These trials are valuable for assessing the real-world impact of interventions, although controlling for confounding factors can be more challenging than in RCTs.

- Ethical Considerations

The manipulation of exposures in experimental studies raises important ethical considerations. Informed consent is paramount, ensuring participants fully understand the potential risks and benefits of the intervention. In some cases, the use of a placebo control may be ethically problematic if an effective treatment already exists. Balancing the pursuit of scientific knowledge with the protection of human subjects is a critical aspect of experimental design.

- Blinding

Blinding, when possible, is a crucial step to minimize bias. Single-blinding involves keeping participants unaware of their treatment assignment, while double-blinding extends this to the researchers administering the intervention. By preventing knowledge of treatment status from influencing outcome assessment, blinding strengthens the validity of experimental findings. For instance, in drug trials, blinding helps ensure that subjective outcomes, such as pain levels, are not unduly influenced by expectations or biases.

Experimental studies, through their rigorous design and controlled manipulation of exposures, contribute significantly to the evidence base of epidemiology. While ethical and practical challenges must be carefully addressed, the insights gained from these interventions play a vital role in informing public health policy and improving health outcomes.

4. Observational Studies

Observational studies constitute a significant category within epidemiological study designs, distinguished by the investigator’s role as a passive observer rather than an active manipulator of exposure. In these methodologies, researchers meticulously collect data on exposures and outcomes without intervening to alter the course of events. The strength of these lies in their capacity to study real-world phenomena, making them invaluable for investigating the etiology, prevalence, and natural history of diseases.

- Cohort Studies: Tracking Risk Over Time

Cohort studies involve following a group of individuals (the cohort) over a period to observe the occurrence of specific outcomes. Participants are categorized based on their exposure status at the study’s outset, and the incidence of the outcome of interest is compared between exposed and unexposed groups. A prime example is the Nurses’ Health Study, which has tracked the health of female nurses since 1976, yielding critical insights into the relationship between lifestyle factors and chronic diseases. The prospective nature of cohort studies allows for the establishment of temporal relationships, strengthening the evidence for causality.

- Case-Control Studies: Retrospective Examination of Disease

Case-control studies compare individuals with a disease (cases) to a control group without the disease to identify prior exposures that may be associated with the condition. Data collection is typically retrospective, relying on past exposure histories. An illustrative example is the investigation of the link between smoking and lung cancer, where researchers compared the smoking habits of individuals diagnosed with lung cancer to those of healthy controls. Case-control studies are particularly useful for investigating rare diseases or those with long latency periods.

- Cross-Sectional Studies: A Snapshot of Health

Cross-sectional studies provide a snapshot of a population at a single point in time, examining the prevalence of diseases and exposures simultaneously. These studies are valuable for assessing the burden of disease and identifying potential associations, but they cannot establish causality due to the lack of temporal sequencing. A national health survey that assesses the prevalence of obesity and related risk factors within a population at a specific time exemplifies this type of methodology.

- Ecological Studies: Population-Level Analyses

Ecological studies examine the relationship between exposures and outcomes at the population level, rather than at the individual level. Researchers might, for instance, compare cancer rates in different geographic regions with varying levels of air pollution. Although prone to ecological fallacy (inferring individual-level associations from population-level data), they can be useful for generating hypotheses and identifying potential environmental risk factors.

The strategic employment of the approaches is vital to inform public health decision-making. By systematically examining the distribution and determinants of health-related states, findings provide the empirical basis for interventions aimed at preventing disease and improving population health.

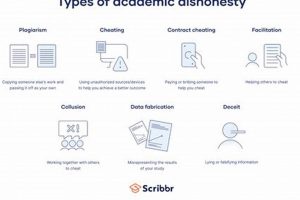

5. Bias Mitigation

Bias mitigation is an indispensable component of rigorous epidemiological study designs. Systematic errors in the design, conduct, or analysis of a study can lead to distorted estimates of the association between exposures and outcomes, thereby undermining the validity of research findings. Therefore, strategies to minimize bias are critical to ensuring that study results accurately reflect the true relationship between variables of interest. For example, in a cohort study examining the effect of a dietary factor on heart disease, selection bias could occur if participants who are more health-conscious are more likely to enroll in the study, leading to an underestimation of the true effect. Similarly, in a case-control study, recall bias could arise if individuals with a disease are more likely to accurately remember past exposures than those without the disease, leading to an overestimation of risk.

The choice of epidemiological study design significantly influences the types of biases that are most likely to occur and the strategies that can be employed to mitigate them. Randomized controlled trials, for example, can minimize selection bias and confounding by randomly assigning participants to treatment groups. However, even in RCTs, blinding can be necessary to reduce performance bias, where knowledge of treatment assignment influences outcome assessment. In observational studies, techniques such as matching, stratification, and multivariable regression are commonly used to control for confounding variables. For instance, when studying the impact of smoking on lung cancer, researchers must account for potential confounding factors like age, sex, and occupational exposures to ensure that the observed association is not due to these other variables. Furthermore, techniques such as sensitivity analysis and E-value estimation can be used to quantify the potential impact of residual confounding and other biases on the study results. Real life application can be seen the design of research and implementation in the study. For example, the research can be used questionare approach to reduce the impact of bias.

In summary, bias mitigation is not merely an adjunct to epidemiological research; it is integral to the scientific process. The selection of an appropriate study design and the implementation of robust strategies to minimize bias are essential for generating valid and reliable evidence that can inform public health policy and practice. Failure to adequately address potential sources of bias can lead to erroneous conclusions, with detrimental consequences for the health of populations.

Frequently Asked Questions

The following addresses common inquiries regarding methodologies and their application in public health research.

Question 1: What distinguishes a randomized controlled trial (RCT) from a cohort study?

A randomized controlled trial (RCT) involves the active manipulation of an exposure by the researcher, with participants randomly assigned to intervention or control groups. This design allows for strong causal inference. In contrast, a cohort study is observational, following groups of individuals with differing exposures over time without intervention. Cohort studies are valuable for establishing temporal relationships but are more susceptible to confounding.

Question 2: When is a case-control study the preferred methodological choice?

A case-control study is particularly useful when investigating rare diseases or those with long latency periods. It retrospectively compares individuals with the disease (cases) to a control group without the disease to identify prior exposures. This design is more efficient than cohort studies for rare outcomes, but it is susceptible to recall bias.

Question 3: How does selection bias affect the validity of study findings?

Selection bias occurs when the individuals included in a study are not representative of the target population, leading to distorted estimates of the association between exposures and outcomes. This can arise from non-random sampling, self-selection into the study, or differential loss to follow-up. Mitigation strategies include using random sampling techniques, minimizing attrition, and accounting for selection processes in the analysis.

Question 4: What is the purpose of blinding in experimental studies?

Blinding, where participants and/or researchers are unaware of treatment assignment, is employed to minimize performance bias and assessment bias. This prevents knowledge of treatment status from influencing outcome assessment, thereby strengthening the validity of the experimental findings. Single-blinding involves keeping participants unaware, while double-blinding extends this to the researchers.

Question 5: How can confounding be addressed in observational studies?

Confounding occurs when a third variable is associated with both the exposure and the outcome, distorting the apparent relationship between them. Confounding can be addressed through various methods, including restriction (limiting the study to individuals with similar levels of the confounder), matching (selecting controls with similar levels of the confounder), stratification (analyzing the association separately within strata of the confounder), and multivariable regression (statistically adjusting for the effects of the confounder).

Question 6: What are the ethical considerations in the design and conduct of these studies?

Ethical considerations are paramount in all epidemiological research. Informed consent is essential, ensuring participants fully understand the potential risks and benefits of participation. Confidentiality must be maintained to protect participants’ privacy. Research protocols should be reviewed and approved by an institutional review board (IRB) to ensure the protection of human subjects and the responsible conduct of research.

Understanding the nuances of methodological approaches is essential for generating credible and actionable evidence in public health. By carefully addressing potential biases and adhering to ethical principles, researchers can contribute to improved population health outcomes.

The next section will delve into emerging trends and future directions in the field.

Conclusion

The examination of various frameworks has underscored their crucial role in understanding health and disease within populations. These methods, encompassing descriptive, analytical, and experimental approaches, provide a systematic means to investigate the distribution, determinants, and prevention of health-related outcomes. A rigorous application of these studies is foundational for evidence-based public health practice.

Continued refinement and judicious application of these approaches are imperative. Future endeavors must prioritize addressing methodological limitations, enhancing data quality, and promoting interdisciplinary collaboration to effectively tackle evolving public health challenges. The ongoing advancement and diligent execution of these studies are vital for improving population health outcomes and safeguarding public well-being.