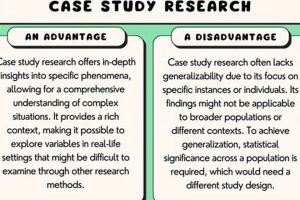

A significant drawback of the in-depth analysis of individual instances is the challenge in generalizing findings to a broader population. The intensive focus on a particular subject, whether it be an individual, group, organization, or event, often results in insights that are highly contextualized and specific. For example, a detailed examination of a successful startup’s innovative strategies may reveal factors contributing to its achievement; however, these same factors might not translate effectively or produce similar results in a different market or organizational setting.

The value of intensive, focused investigation lies in its capacity to reveal complex interactions and nuanced details that might be missed in larger-scale studies. Historically, such focused investigations have provided valuable groundwork for theory development and hypothesis generation. They offer rich, descriptive data that can inform the design of subsequent quantitative research. However, the lack of statistical power and the potential for researcher bias inherent in this methodology necessitate caution when extrapolating conclusions beyond the boundaries of the specific case examined.

Consequently, while valuable for exploratory research and generating hypotheses, it is crucial to acknowledge the limited scope of inference. This characteristic necessitates the careful consideration of alternative research designs when seeking to establish broad, generalizable principles. The inherent constraints on external validity highlight the need to complement this approach with methodologies capable of producing more robust and widely applicable findings.

Mitigating Generalizability Concerns in Case Study Research

Addressing the challenge of limited generalizability in case studies requires a multi-faceted approach. Careful planning and execution can enhance the potential for wider applicability of findings, despite the inherent limitations of the methodology.

Tip 1: Employ Theoretical Frameworks: Utilize established theoretical frameworks to guide the research design and analysis. This provides a structure for interpreting findings and relating them to broader bodies of knowledge, increasing the potential for transferability.

Tip 2: Select Representative Cases: While random sampling is not feasible, strive to select cases that are theoretically relevant and representative of the phenomenon under investigation. Document the rationale for case selection, highlighting similarities and differences with other potential cases.

Tip 3: Provide Thick Description: Offer detailed and nuanced descriptions of the context, processes, and outcomes of the case. “Thick description” allows readers to assess the degree to which the case resonates with their own contexts and make informed judgments about transferability.

Tip 4: Use Multiple Cases: Employing multiple case study designs can enhance generalizability by identifying patterns and variations across different contexts. Replication logic, where similar results are expected across cases, strengthens the argument for broader applicability.

Tip 5: Conduct Cross-Case Analysis: When using multiple cases, systematically compare and contrast findings across cases to identify common themes, unique features, and potential contextual factors influencing outcomes. This strengthens the analytical rigor and enhances the potential for drawing more generalizable conclusions.

Tip 6: Acknowledge Limitations: Clearly acknowledge the limitations of the case study approach, particularly regarding generalizability. Explicitly state the scope of the findings and the contexts in which they are most likely to be applicable.

Tip 7: Triangulate Data: Employ multiple sources of data (e.g., interviews, documents, observations) to corroborate findings and enhance the validity of interpretations. Triangulation strengthens the credibility of the case study and increases confidence in the findings.

By implementing these strategies, researchers can enhance the value of case study research despite the inherent challenges to generalization. While case studies may not provide statistically generalizable results, they can offer valuable insights and inform the development of more generalizable theories and interventions.

Acknowledging and addressing the limits of broader applicability is a crucial aspect of rigorous case study research. Moving forward, consider these approaches to contextualize the findings properly.

1. Limited scope

The restricted nature of case studies, defined by their in-depth investigation of a singular instance or a small group of instances, fundamentally contributes to the central challenge of generalizability. The detailed insights gained are often deeply intertwined with the specific context, making direct transference to broader populations or different settings problematic.

- Sample Size Constraints

The inherent limitation of a small sample size, often a single case, drastically reduces statistical power. Consequently, observed relationships and patterns within the case may not be representative of the larger population, and any attempt to extrapolate findings risks overgeneralization. For instance, a study of a single highly successful project management team, while informative, cannot reliably predict the performance of other teams in different organizational contexts or industries.

- Contextual Dependence

Case studies are profoundly influenced by their specific environment, including organizational culture, industry dynamics, and historical events. These contextual factors create unique conditions that may not be present elsewhere. A case study examining the implementation of a new technology in one company, for example, might uncover successes attributed to a pre-existing infrastructure that is not typical across the industry, limiting the applicability of the findings.

- Selection Bias

The criteria used to select cases can introduce bias, as researchers may consciously or unconsciously choose instances that are perceived as particularly interesting or successful. This non-random selection process compromises the representativeness of the sample. Studying only “best-case” scenarios, for instance, provides an incomplete picture and may neglect critical insights from less successful or more typical situations.

- Replication Challenges

The intensive, qualitative nature of case study research often makes replication difficult. Even with detailed descriptions of the methods and context, replicating a case study exactly is virtually impossible due to the uniqueness of each setting and the potential for subjective interpretations. This lack of replicability further restricts the ability to generalize findings with confidence.

In conclusion, the convergence of small sample sizes, contextual dependence, selection bias, and replication challenges underscores the limited scope. The intrinsic restraints demand a cautious approach to drawing broader conclusions, highlighting the necessity for additional confirmatory research using methodologies that offer greater statistical power and generalizability. Case study insights should be considered as potential hypotheses to be rigorously tested rather than definitive conclusions applicable across diverse contexts.

2. Context specificity

Context specificity is a critical element directly impacting the generalizability of case study findings. The intricate details of a particular situation, encompassing its historical, cultural, economic, and social dimensions, contribute to the distinctiveness of the case. This embeddedness complicates the transference of insights to other environments.

- Unique Environmental Factors

The surrounding circumstances, which include geographical location, competitive landscape, and regulatory environment, can exert substantial influence. A case study examining a business strategy’s success in a specific regional market may not hold true for other markets due to varying consumer preferences, infrastructural differences, and economic conditions. For instance, a marketing campaign that resonates effectively in one cultural context might be ineffective or even offensive in another, severely limiting the broad applicability of the observed outcomes.

- Organizational Culture and Structure

Internal characteristics, such as the organization’s leadership style, values, communication patterns, and internal processes, significantly shape the dynamics within a case. The success of an innovation initiative in a highly collaborative and agile organization may not be replicable in a more hierarchical and bureaucratic setting. The specific interplay of these factors creates a unique internal ecosystem that restricts the extrapolation of findings to organizations with differing cultures.

- Temporal Dependence

The point in time at which a case study is conducted plays a crucial role, as circumstances evolve and historical events shape the landscape. A policy intervention that proves successful during a period of economic stability may yield different results during a recession or a period of rapid technological change. The temporal context defines the conditions under which the case unfolds, rendering its outcomes time-sensitive and potentially irrelevant in different eras.

- Stakeholder Influence and Relationships

The network of stakeholders involved, including customers, suppliers, employees, and community members, contributes significantly to the case’s dynamics. The nature of the relationships, the power dynamics among them, and the level of engagement can influence outcomes substantially. A successful project that benefits from strong stakeholder support and collaboration may not achieve the same results in situations where these relationships are weak or conflicting. The peculiarities of stakeholder interactions thus act as a contextual constraint on generalizability.

The convergence of unique environmental factors, organizational culture, temporal dependence, and stakeholder influences collectively underscores the challenge. The interwoven nature of these contextual elements demands a nuanced understanding of the specific case, cautioning against the uncritical application of findings to contexts that lack the same constellation of attributes. Recognition of these limitations is paramount when interpreting and applying case study insights.

3. Unique circumstances

The presence of unique circumstances in a case study significantly compounds the problem of generalizing findings. These atypical conditions, which can range from unusual market conditions to idiosyncratic organizational structures, render the case less representative of broader populations or settings, directly contributing to limitations in external validity.

- Uncommon Market Conditions

A case study might examine a company’s success in a niche market or during a period of unusual economic growth. The strategies employed and the outcomes achieved under these conditions may not be transferable to more competitive or economically constrained environments. For example, a company’s rapid expansion during a tech boom might not be replicable during a period of market consolidation or recession.

- Idiosyncratic Organizational Structures

The specific organizational structure, leadership style, or internal culture of a featured entity can contribute to unique circumstances. A case study focusing on a company with a highly innovative and decentralized organizational structure may not provide insights applicable to more traditional, hierarchical organizations. The practices that thrive in one specific context may not be easily adopted or effective in a different organizational framework.

- Atypical Resource Availability

The availability of unique resources, such as access to specialized talent, proprietary technology, or significant capital investment, can create circumstances that are not commonly found. A study of a research institution benefiting from substantial government funding might not offer practical guidance to institutions with limited financial resources. The presence of these atypical resource levels restricts the applicability of findings to settings with more constrained resources.

- Exceptional Leadership or Talent

The presence of exceptional leadership or highly skilled individuals can significantly influence outcomes in a specific case. A case study showcasing the turnaround of a struggling company under the guidance of a charismatic and visionary leader may not offer insights that are easily transferable to organizations lacking similar leadership capabilities. The extraordinary skills and attributes of key personnel can create unique circumstances that limit the generalizability of the findings.

These unique circumstances, stemming from market anomalies, organizational idiosyncrasies, resource advantages, or exceptional personnel, collectively undermine the potential for broad generalization. Researchers must carefully consider these factors when interpreting case study findings and acknowledge the limitations they impose on external validity. Recognizing the context-specific nature of the case is paramount in determining the appropriate scope and application of the derived insights.

4. Researcher bias

Researcher bias represents a significant threat to the validity and generalizability of case study findings. The subjective nature of data collection and analysis in case study research makes it particularly susceptible to the influence of the researcher’s preconceived notions, expectations, and personal beliefs, which can compromise objectivity and distort the interpretation of the case.

- Selection Bias in Case Choice

Researchers may unconsciously or consciously select cases that align with their pre-existing hypotheses or expectations. This non-random selection process can lead to the overrepresentation of cases that support a particular viewpoint, thereby skewing the overall findings. For instance, a researcher studying the effectiveness of a specific leadership style might selectively choose cases of successful companies led by individuals who exemplify that style, neglecting to examine cases where the same leadership style yielded less favorable outcomes. This biased selection undermines the representativeness of the case and limits the generalizability of any conclusions drawn.

- Confirmation Bias in Data Collection

During data collection, researchers may selectively attend to information that confirms their pre-existing beliefs while disregarding or downplaying contradictory evidence. This confirmation bias can lead to a distorted understanding of the case, as the researcher may only focus on aspects that support their initial assumptions. For example, in studying the implementation of a new technology, a researcher who believes in its efficacy might emphasize positive user feedback and overlook or minimize reports of challenges or usability issues. Such selective reporting can significantly compromise the validity of the case study findings.

- Subjective Interpretation of Qualitative Data

Case study research often relies on qualitative data, such as interviews and documents, which are subject to interpretation. Researchers may unconsciously interpret this data in a way that aligns with their pre-existing beliefs, leading to a biased understanding of the case. For instance, when analyzing interview transcripts, a researcher might selectively highlight quotes that support a particular narrative while downplaying or reinterpreting quotes that contradict it. This subjective interpretation can introduce bias and limit the objectivity of the analysis, making it difficult to generalize the findings to other contexts.

- Bias in Report Writing and Presentation

The way a researcher presents the findings of a case study can also be influenced by bias. Researchers may selectively emphasize certain aspects of the case or frame the results in a way that supports their pre-existing viewpoints. For example, a researcher might focus on positive outcomes and downplay challenges or limitations in the report, creating an overly optimistic picture of the case. Such biased reporting can mislead readers and undermine the credibility of the research, limiting the extent to which the findings can be generalized to other situations.

The multifaceted influence of researcher bias, stemming from case selection, data collection, data interpretation, and report presentation, significantly contributes to the central limitation of generalizability. The subjectivity introduced by these biases can compromise the objectivity and validity of case study findings, restricting their applicability to broader populations or different contexts. Addressing and mitigating researcher bias is thus crucial for enhancing the rigor and credibility of case study research.

5. Lack of statistical power

A fundamental impediment to generalizing findings from case studies arises from the inherent lack of statistical power. Case studies, by their very nature, typically involve the intensive examination of one or a small number of instances. This limited sample size precludes the application of statistical tests designed to establish the broader validity of observed relationships. As a result, even if a compelling association is identified within the case, it remains uncertain whether that association is genuinely representative of the larger population from which the case was drawn, or simply a chance occurrence.

The absence of statistical power has several practical consequences. For example, a case study of a successful organizational turnaround attributed to a specific leadership intervention may be highly persuasive at the level of that single organization. However, without the ability to demonstrate statistically that similar interventions lead to similar outcomes across a larger sample of organizations, the findings remain tentative and cannot be confidently applied to other contexts. The inability to quantify the strength and consistency of an effect severely restricts the external validity of case study conclusions. Furthermore, it impedes the ability to control for confounding variables, increasing the risk that observed associations are spurious rather than causal. Therefore, conclusions drawn from case studies should be regarded as hypotheses warranting further investigation through methods with greater statistical rigor, rather than definitive pronouncements of broadly applicable principles.

In summary, the inherent lack of statistical power in case study research directly contributes to its primary limitation: difficulty in generalization. While case studies can provide rich, detailed insights and generate valuable hypotheses, the inability to statistically validate these hypotheses significantly restricts their applicability to other settings. Understanding this limitation is crucial for appropriately interpreting case study findings and for designing research strategies that can overcome this challenge.

6. Sampling issues

Sampling issues in case study research directly contribute to the major limitation of difficulty in generalization. The process of selecting cases for intensive analysis often involves non-random sampling techniques, which introduces biases and limits the representativeness of the selected cases. This non-representative selection undermines the ability to draw inferences that can be reliably applied to broader populations or different contexts. For example, if case studies are selected based on their perceived “success” or “uniqueness,” the findings may not reflect the experiences of more typical instances, thus restricting the applicability of the conclusions. The very act of choosing particular cases over others introduces a potential source of systematic error, leading to biased results and reduced external validity. The small number of cases typically involved exacerbates this problem, further limiting the statistical power and the potential for generalization.

Furthermore, the absence of a rigorous sampling frame makes it difficult to determine the extent to which the selected cases are representative of the broader population of interest. This lack of a well-defined sampling frame impedes the ability to assess the potential for selection bias and to control for confounding variables. Consequently, even if a compelling relationship is observed within the selected cases, it is difficult to confidently assert that the relationship would hold true in other settings or with different populations. The absence of a systematic sampling strategy therefore introduces a degree of uncertainty that fundamentally undermines the generalizability of case study findings. The issues highlight the need for carefully justifying case selection and acknowledging the potential limitations arising from the sampling strategy.

In summary, sampling issues, including non-random selection and the absence of a rigorous sampling frame, constitute a significant component of the challenge to generalize findings from case studies. Addressing these sampling issues through careful selection criteria and explicit acknowledgment of limitations can mitigate, but not entirely eliminate, the threats to external validity. Case study research, despite these inherent sampling constraints, provides valuable insights that can inform hypothesis generation and theory development, even as the broader applicability of specific findings remains subject to caution.

7. Replication difficulty

Replication difficulty directly exacerbates the main drawback of case studies: limited generalizability. The inherent complexities and contextual dependencies within individual cases make it exceedingly challenging to replicate the study design and conditions in other settings, thus hindering the validation and broader applicability of the findings.

- Contextual Uniqueness

Each case study is embedded in a specific context characterized by unique historical, social, and organizational factors. These factors cannot be easily replicated, making it difficult to determine whether the observed outcomes are attributable to the intervention being studied or the specific contextual elements. For example, replicating a case study on a successful organizational change initiative would be challenging if the initial study occurred during a unique economic upturn or involved specific individuals with rare skill sets.

- Qualitative Data Interpretation

Case studies often rely on qualitative data, such as interviews, observations, and document analysis, which are subject to subjective interpretation. Different researchers may interpret the same data in different ways, leading to inconsistent findings and hindering the replication process. The nuances and subtleties captured in qualitative data can be difficult to codify and standardize, making it challenging to ensure that the same phenomena are being measured and interpreted consistently across different replications.

- Researcher Influence

The researcher’s presence and interactions with the case study subject can influence the data collection and analysis process. The researcher’s personal biases, assumptions, and interpretations can shape the narrative of the case, making it difficult to separate the objective reality from the researcher’s subjective perceptions. Replicating a case study with a different researcher may lead to different findings due to variations in researcher influence, thus undermining the validity and reliability of the results.

- Dynamic and Evolving Nature of Cases

Case studies often examine phenomena that are dynamic and evolving over time. The conditions and circumstances surrounding the case may change, making it difficult to replicate the study at a later date. For example, a case study on a successful product launch may be difficult to replicate if the market conditions have changed significantly since the initial launch. The dynamic and evolving nature of cases introduces a temporal element that makes replication challenging.

The challenges stemming from contextual uniqueness, qualitative data interpretation, researcher influence, and the dynamic nature of cases collectively contribute to replication difficulty. This difficulty, in turn, severely limits the generalizability of case study findings, as the lack of replicability undermines confidence in the broader applicability of the observed relationships. The convergence of these factors highlights the need for caution when extrapolating conclusions from case studies to other settings and populations.

Frequently Asked Questions Regarding Generalizability in Case Study Research

This section addresses common inquiries concerning the challenges associated with extending conclusions drawn from case study investigations to broader contexts.

Question 1: Why is generalizability considered a significant limitation of case studies?

The intensive nature of case study research often focuses on specific instances, rendering it difficult to ascertain whether observed findings are applicable beyond the boundaries of the case itself. The limited sample size inherent in this methodology restricts the statistical power necessary to draw broader inferences.

Question 2: How does the context-specific nature of case studies affect generalizability?

Case studies are deeply embedded within unique historical, cultural, and organizational contexts. These contextual factors influence the observed phenomena, making it challenging to determine whether the findings are transferable to different environments lacking the same attributes.

Question 3: In what ways does researcher bias influence the generalizability of case study results?

The subjective nature of data collection and interpretation in case study research can introduce bias. Researcher’s preconceptions and expectations may influence the selection of cases, the analysis of data, and the presentation of findings, thereby compromising objectivity and limiting the broader applicability of the results.

Question 4: Can multiple-case study designs overcome the limitation of generalizability?

Employing multiple cases can strengthen the potential for generalization by identifying patterns across different contexts. However, the selection of cases and the analytical methods employed remain crucial in determining the extent to which findings can be confidently extended beyond the specific cases examined. Replication logic is essential.

Question 5: What strategies can be employed to mitigate the challenges to generalization in case study research?

Researchers can enhance the potential for wider applicability by employing theoretical frameworks, selecting representative cases, providing detailed descriptions, and acknowledging limitations. Triangulation of data sources and rigorous analytical techniques can also improve the credibility and transferability of findings.

Question 6: How should case study findings be interpreted in light of the limitations to generalizability?

Case study results should be viewed as hypotheses requiring further investigation. While case studies can provide valuable insights and inform theory development, caution should be exercised when extrapolating conclusions to other settings without additional empirical support. Findings should be contextualized appropriately.

In conclusion, the challenges to achieving broad applicability should be conscientiously considered when evaluating case study research. Understanding these limitations is essential for responsibly applying the insights gained from in-depth investigations of individual instances.

Acknowledging the limited scope is a fundamental step to use case studies for exploratory research and hypothesis generation.

Conclusion

The preceding exploration has illuminated that the major limitation of case studies is generalizability. The intrinsic nature of intensive, localized investigation inherently restricts the extent to which findings can be reliably extended to broader populations or divergent contexts. Factors such as contextual specificity, researcher bias, lack of statistical power, sampling issues, and replication difficulty collectively contribute to this limitation. While case studies offer valuable insights into complex phenomena and can serve as a foundation for hypothesis generation, the application of findings beyond the specific case requires judicious consideration.

Therefore, it is essential that researchers and practitioners approach case study results with a critical awareness of their inherent limitations. Subsequent research employing methodologies capable of establishing broader validity is often necessary to confirm or refute hypotheses derived from case study analyses. Acknowledging and addressing these limitations is crucial for responsible knowledge dissemination and informed decision-making in academic, professional, and policy spheres.